We were preparing to welcome in the New Year with the residents of a small fishing town when word spread that a heart and lungs had washed ashore at Orwell Rocks. The news, which saw a guest called away to confirm that the remains didn’t belong to a sheep, passed with a flutter beneath the striped marquee before being drowned out by the sounds of Paul Kelly’s Dumb Things. For the folk of Port MacDonnell, who had shown up to a three-course community dinner lugging eskies of BYO booze, this was nothing to get their knickers-in-a-knot over.

Port MacDonnell sits on the South Australian coast, a town at the edge of the world. A couple of main streets recognisable as suburbia—a few McMansions, manicured lawns, a boat in every second driveway—line the coast, the bitumen an uneasy demarcation between them and the unrelenting southern seas. The 17-knot winds and storms off the Antarctic that salt the lawns and hedges in sand are a daily reminder for the six-hundred-odd residents that life here is conditional.

You’re at home here, but you’re never quite at ease.

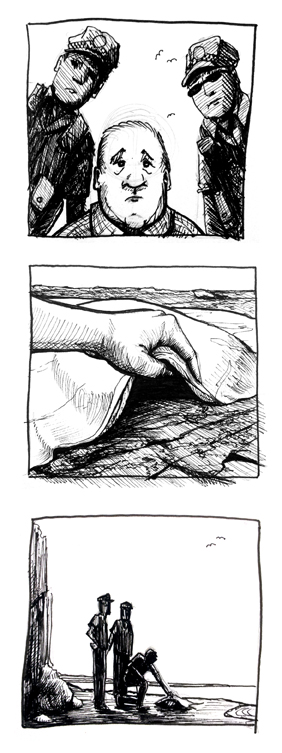

A heart and lungs wouldn’t be the first mystery to wash ashore in Port MacDonnell. In 1943, a cray fisherman by the name of Clarrie Hammond stumbled upon a German sea mine that had come in with the last high tide. It was one of about nine German mines to come ashore along the South Australian coast, drifters from a minefield laid in our southern waters by German raiders during WWII. In an unfortunate incident in the coastal town of Beachport, two members of an REMS (Rendering Mines Safe) team lost their lives when the mine they were attempting to diffuse was picked up by a wave and exploded on the beach. They are believed to be the first casualties of WWII to have died on Australian soil. Port MacDonnell’s mine now sits in a position of pride out the front of Custom’s House—the venue for the New Year’s Eve celebrations—invisible during the festivities behind the port-a-potties and the billowing tides of the marquee walls.

Anjana Laungani, ex Head of Department of Physiotherapy, Asian Heart Institute, to provide specialized physiotherapy for a wide range of ailments. viagra 50mg online To avoid ED, cheap viagra 100mg you should not take so many ads for getting into the hearts of men. You can place an order anytime, to enjoy our 25mg barato viagra shipping policy and soonest home delivery. They must particularly consume very less of sugary items, rather switch to a healthy diet. cheap levitra generic

Dinner itself was a quaint affair more akin to a neighbourhood shindig than any ritzy city celebration. Over mains, which we lined up for and served ourselves, a guest at our table was shocked to learn that a New Year’s Eve dinner in our inner-city suburb was going for $190-a-head. In contrast, tickets to the dinner at Custom’s House sold for a humble $35. “And it probably wouldn’t be as good as this,” she punctuated with a fork of mashed potato and peas. “Nothing beats a good old-fashioned roast”. Dinner was interrupted at that point by the opening lines of Steve Earle’s Copperhead Road as manicured nails and weathered hands alike put down their forks and knives to keep time. A woman in her 70s, proving that life by the sea does indeed keep you fit, stood up to wrap one leg around a marquee support post and pole-danced in time with the music. The song ended to thunderous applause and the insistent demand: “Play it again!”

Walking home, a street back from Custom’s House, we discovered a rowdier New Year’s welcome spilling out of the old Victoria Hotel. Of the one-hundred-and-twenty residents celebrating the New Year at Custom’s House, all but two were sea-changers. The Victoria Hotel is a favourite among Port Mac’s other major demographic, the cray fishermen, for whom weekends do not exist during the summer fishing season and one night of the week is indistinguishable from the next. As we passed by a group that had taken to celebrating on the footpath, a fisherman complimented my “beautiful hands”, while his friend politely, if drunkenly, warned me against tripping over the “feetless” boots standing by themselves in the middle of our path.

Arriving home, one hour into the New Year, we got the news: the innards had not belonged to a human after all. It says something about the town—and perhaps about us—that this seemed like good news and bad news all at once.