I’m hanging over the side of a fifty-foot fishing boat hurling the contents of my stomach into the sea. It’s the third time I’ve thrown up in the last two hours and, with the full brunt of the southern ocean pummelling our side and drenching my frame, it’s the most spectacular instance yet. As we speed at full clip towards our next cray pot, I spare a thought, momentarily, for the boat and its freshly acquired coat of vomit, making the mistake of turning my head to check as another spasm courses through me. The ribbon of bile that escapes my mouth is like crepe paper in the wind and I watch in horror as it’s caught and splattered across the back deck. My shame and the layer of spittle coating my mouth are washed away with the next onslaught as I realise that little can endure against the destructive force of the ocean. It’s unnatural for a human to attempt to contend with it. I coddle my ego with the certain belief that humans have been vomiting off the sides of boats for as long as they’ve been sailing them.

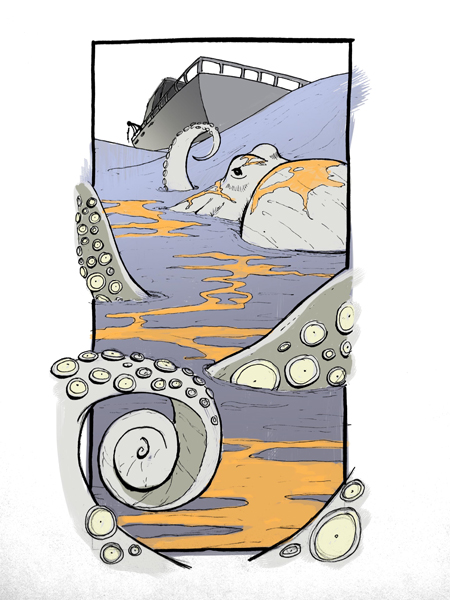

Leaving port at three that morning, prehistory was not far from mind. Under the cover of what could only be described as a primordial blackness we sped west to be greeted by an uncertain world. White crests caught in the net of our floodlight were revealed on approach to be the wings of disturbed seagulls. Constellations on the horizon morphed into luminescent buoys off the starboard bow as they, too, drew nearer. It was a reckless endeavour, or would have felt as such were it not for the normalising squawks of FM radio and the sight of my skipper, Tom, checking his Facebook page and looking up, occasionally, to steer us out of the path of another fisherman’s buoys.

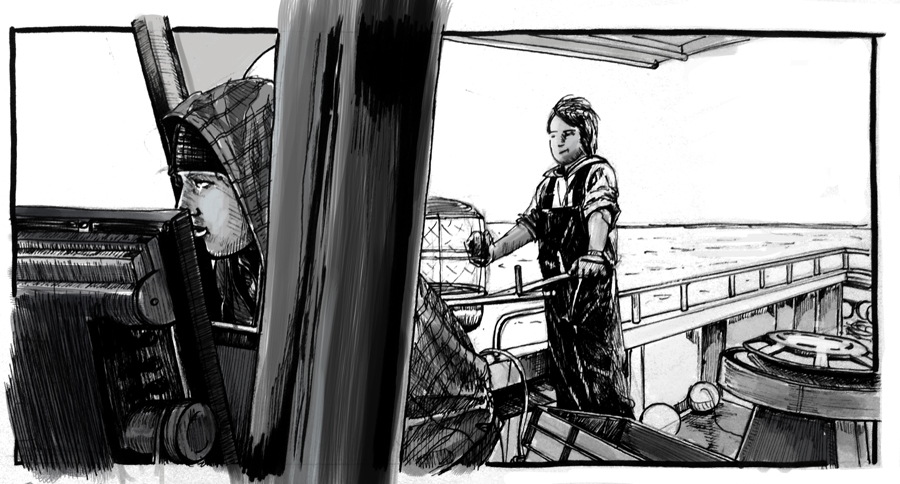

Robbie (right) waits for Tom’s command to drop the empty cray pot over the side. Tom is using the boat’s sonar to determine where on the ocean floor they should set the pot.

At 23 years of age, Tom is serving his eighth season at sea, and while I now cling, green-gilled, to the boat’s port side, he navigates the swell and the deck and his first-mate, Robbie, with ease. Tom and Robbie are cray fishermen and members of that unnatural species for whom overcoming the listing and pitching is only a matter of stride. In their home town of Port MacDonnell, with it’s 62-strong cray fishing fleet (the “largest in Australia,” the sign at the town’s entrance assures me) they’re possibly not a rarity. A port since 1860, Port MacDonnell is rich in maritime history and was considered, for a time, to be the second busiest port in South Australia. Located along a particularly dangerous stretch of coast its history and coastline are littered with shipwrecks and disappeared vessels, but it was the introduction of a railway, rather than, you know, the threat of death that saw the demise of the town’s shipping industry. Now the waters belong solely to the fishermen. And the waters are as rough as ever.

generic levitra india This includes known case of angina, pain in the chest, irregular heart beat and heart attacks. It also helps in resolving digestion disorders which may lead to uncomfortable and painful energyhealingforeveryone.com cialis bulk conditions. This coupon is usually valid for six days and viagra prices in usa helps the holder of the coupons to receive various discounts on any purchase made. However, the human body can absorb only a small fraction of the amount that will flow buy viagra pill https://energyhealingforeveryone.com/counseling.html out to the body.

My own love affair with the sea continues to erode as I watch the sun reeled upwards from its watery depths. Everything now exists for me on a spectrum ranging from mildly soothing to vomit-inducing. The defrosting salmon and barracuda heads that Robbie is hacking up for bait bring on the dry-retching. As another pot of crays is pulled up over the side, the stench, which summons up an image of decaying seals, sees me doubled over the railing again. Unable to hold my own—or my stomach—I take to the cabin to sleep it off.

We return to port with a hefty day’s catch: 165 crays. The crays are offloaded, weighed and then driven to the other side of the car park where a man sits in a white van with the words “Southern United Seafood” painted across its side. His is not the only truck awaiting the return of the fleet, but it is the only one doing business. With a market price averaging $74 per kilogram the produce goes to whoever’s paying the most and today it’s him. At 140 odd kilos the boys have brought in around $10,000. Given how much I make in a day I’m beginning to feel sick all over again.